Does anyone else every hear about tone (or tonal) languages, or is that just something that us language nerds hear about? I’m actually curious, because it seems to me to be something that everyone hears about every once in a while, but then I’ve heard things recently that make me rethink that assumption. So feel free to post a comment below and let me know.

But whether or not you ever talk about or hear about tonal languages, I do. And most of the time what people seem to say about them is, “It’s like Chinese.” It’s true, Chinese language varieties (that’s a fancy way of saying “languages” or “dialects” without having to pick which word to use) are the most well-known tone language(s) to Americans. But did you know that over half of the world’s languages are tonal? So what does that mean? I’m glad you asked!

Here’s an exercise to help you discover it yourself. Say these two sentences out loud:

1. I love unbas. 2. I love unbas?

Can you hear the difference in how you pronounce the two “unbas?” Most American English speakers should make the first sentence end kind of low and the second end kind of high. Is that what you did? Great! Now, say them again, and this time, say the “I love” parts in your head and just pronounce the “unbas” part out loud. Did you hear how they sound different? For us, it just sounds like one is a question and one is a statement. But in some languages, that difference in pitch means that they would be two different words. So, leaving off how to write it, imagine if your dictionary said something like this:

Unbas (as pronounced in 1 above): donkeys. Unbas (as pronounced in 2 above): mothers-in-law.

Kind of important how you pronounced it, right? That’s a distinction you want to be sure to make correctly! And that’s one of the main ways that some tone languages, especially Asian ones, work.

But there are lots of other things that tone can do, too! Here’s an example of one of the many things that it often does in African tone languages. Say these two sentences out loud:

1. I eeyah it. 2. I eeyah it?

You’re probably getting really good at tone now and can hear the difference between those two sentences, right? Ok, now imagine that the verb “eeyah” means “to throw.” But imagine also that the difference in tone is a difference between past tense and present tense. So the first sentence meant, “I threw it,” and the second one meant, “I throw it.” Now, if you’re really good at this stuff, you may notice that the tone of the “eeyah” changed, and so did the tone of the “it.” And part of that is because of the example and how the English language works, but I didn’t try to fix the example, because tones in many languages also affect the words around the word with the tone change. So the change of the “eeyah”s would change how you’d pronounce the “it,” too. Crazy, huh?

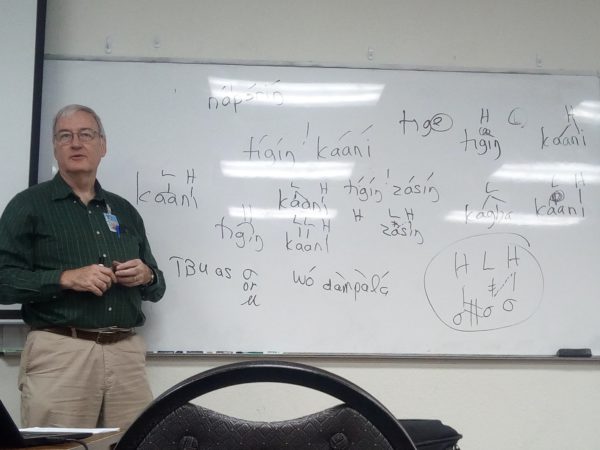

Now, I don’t know exactly how the language that I’m learning uses tone. But it probably is a tonal language, since I believe all the other languages in its language family are. Someone said that it may use tone more like in the second example, and that tone may make a difference between past tense and present tense. I’m not good enough at it to know yet. But those are the kinds of things we’re learning in my tone class, and, as scary as the picture looks, one thing that we’re learning is that tone is weird, but it doesn’t have to be scary. And that’s a very encouraging thought.

Thank you Susie for today’s lesson!! Interesting. Didn’t understand ‘tonal’ before. Keep up the good work ….. blessings, marie.

So, for tonal languages (like the donkey example) where the same word can mean two separate things based on the sound, when it’s written do you have to tell based on the context which word is being used (like “lead” the verb and pencil “lead” in English)?

Jeff, where the two different words can have different meanings based on the pitch, you usually do something in the alphabet to show the different pitches of the words. In Africa it’s usually accent marks, so, for example, é could mean that it’s an “e” that’s pronounced at a higher pitch, and è could mean that it’s an “e” pronounced at a lower pitch. But there are lots of other factors that come into play as well, so it doesn’t always work out quite that nicely.

There are some tonal languages that don’t have to write tone in their alphabet because it can be figured out from the context, but, as we learned in class today, it’s probably better in a tonal language to assume that you should write tone somehow in the alphabet unless there is clear evidence that you don’t have to.

Great question!

Thank you for explaining “tonal” because I really had no clue.

I thank God for people like you whom He has placed an interest in learning a new language so you can bring the Good News to a people group needing to know about our Savior.